Capitalism Under Fire

For over twenty years, the Edelman Trust Barometer has surveyed tens of thousands of people on various issues, from business to politics to the environment. In 2020, the survey found that only 18% of the respondents felt capitalism was working for them. 56% of the respondents said that capitalism, as it exists today, does more harm than good in the world. Even in the U.S., the temple of capitalism, 47% of the respondents felt capitalism does more harm than good[1]. Reading the news, one could be sympathetic to those views. Rising inequality, greed and corruption, and environmental degradation are just some of the ills that we blame on capitalism.

However, I believe the reality is more nuanced. While it’s not perfect, capitalism, at least the version built on a free and competitive market, is the most effective system of allocating resources. In a resource-constrained world, any system that increases the efficiency of resource allocation will bring about greater material abundance. When that abundance is widely shared, it leads to increasing prosperity and tangible benefits to the lives of many people, but when abundance is captured by a narrow elite, the misery for the rest increases. When we look at history, there have been periods when capitalists and politicians worked together to capture all the gains for themselves, but there have also been times when enlightened capitalists shared their success with their workers and communities. There were even cases when capitalists fought for desegregation, gender equality, and the rights of minorities[2].

What we do with the fruits of capitalism is a moral choice. Since the Enlightenment, there has been a trend of de-emphasising morality in public discourse for the fear that it will lead to orthodoxy and infringe on individual liberty[3]. However, this is a false dichotomy. We should be able to have respectful discussions about ethics without descending into morality policing. If the general public isn’t permitted to debate ethics, then the void will only be filled by fundamentalists with extreme views. How we should think about ethics and business will be a topic for future articles. In the rest of this article, I will make a case that capitalism, when done properly, can create tangible benefits to people’s lives.

The Rocket

On Tuesday, 6th October 1829, more than 10,000 people gathered on the eastern side of the Rainhill Bridge, about ten miles outside of Liverpool. Over the next few days, five locomotives (one of them was actually two horses on a walking belt) competed on a one-mile track. Robert Stephenson’s “The Rocket” was the only locomotive to complete all the trials, winning the prize of £500 (worth more than £50,000 in today’s value). At one point, The Rocket sped along the track at more than 30 miles per hour, impressing one reporter from The Times, who compared it to a swallow darting through the air[4].

Robert Stephenson and his father, George Stephenson, were already reputable engineers at the time, but their success at the Rainhill trials cemented their place in history. The Rocket kickstarted the Railway Revolution. It transformed how people travelled and how goods were transported. The Stephensons would be rightly remembered for their engineering brilliance. However, behind the scientific and technological advancements, the lives of the Stephensons also reflected the profound changes in how people lived.

Robert Stephenson’s grandfather, Robert Stephenson Sr., known to his friends as “Old Robert Stephenson”, worked as a fireman in various mining pits in Northumberland until one day, an accident made him blind, and he had to rely on others for his daily bread. In his younger days, Old Robert married Mabel Carr, the daughter of a bleacher and dyer from a village on the bank of the River Tyne. While Mabel’s mother came from a wealthy family, when her father found out she was marrying a bleacher and dyer, he turned his back on her, leaving her with nothing upon his death. Old Robert and Mabel both grew up with very little. J.C. Jeaffreson and William Pole, contemporaries of Robert Stephenson, wrote in their book about the engineer, “There is no doubt that the grandfather of the greatest engineer of the present century lived and toiled and died in humble circumstances.”[5]

Old Robert and Mabel had six children: four sons and two daughters. One of them was George Stephenson, father of Robert Stephenson. George was born in 1781. Like many pit children, he grew up illiterate. However, he was honest and sober in character. In 1801, George became the brakesman of the engine of the Dolly Pit in Black Callerton. There, he met Frances Henderson, known as Fanny, who was a servant in the house where George was staying. In November 1802, George and Fanny were married. Eleven months later, Fanny gave birth to a son, Robert, named after his grandfather[6].

Robert brought happiness to the Stephenson family, and there was every evidence that his father loved him dearly. Sadly, shortly after Robert’s birth, Fanny contracted tuberculosis. Further tragedy struck when George and Fanny’s second child, a daughter, died in 1805, only three weeks after her birth. A year later, tuberculosis took Fanny’s life. The adversity only motivated George to work harder. In addition to his day job, the young father spent his evenings making shoes and learning about mechanics. By then, George had taught himself to read.

Knowing the value of learning, George was adamant that his son would receive a different upbringing. He sent Robert to a local school. Every day, Robert walked over a mile to his school[7]. As he got older, Robert would pick up odd jobs, such as taking pitmen’s tools to the smith on his way to and from school. Nevertheless, his father insisted that Robert “should not commence the real battle of life” until he has mastered writing and reading[8].

In 1812, George was promoted to the engine-wright of Killingworth Colliery, with a salary of £100 per annum. In addition to his salary, George also derived a decent income from servicing the clocks of his workers and local farmers. As an engineer at Killingworth, George paid careful attention to the technological advancements that were happening around him. When he saw that a steam engine running on smooth rails could drag along loaded carriages, he became sufficiently impressed that he decided to construct his own locomotives. On 25th July 1814, George Stephenson’s locomotive successfully ran on the Killingworth line for the first time. This feat caught the attention of a local businessman, Mr. Lush, who offered George a second job, working two days a week at his ironwork for £100 per annum. With approval from his first employer, George now had two concurrent jobs and doubled his income. He took Robert out of the village school and sent him to an academy in Newcastle as a day pupil.

In 1819, Robert Stephenson left school and became an apprentice to a mining engineer. At the same time, his father began constructing his first railway at the Hetton Colliery. In 1820, George Stephenson married for the second time, to Elizabeth Hindmarsh. Next year, father and son worked together to survey the Stockton and Darlington Railway. George was the chief engineer, and Robert was his assistant. Several people were impressed by Robert’s talent and suggested to George that he should receive a college education. George could have afforded to send his son to Cambridge. However, he didn’t want Robert to become a gentleman but to do real work. Hence, Robert spent a few months in Edinburgh[9].

In 1823, with a few backers, George Stephenson established a new manufacturing firm. As a sign of his paternal devotion, he made Robert a partner in the firm and named the company Robert Stephenson and Co.[10] After a few years in Columbia, where an attempt to develop a mining business ultimately failed, Robert returned to Newcastle in 1827 to continue his work on locomotives. At that time, locomotives were slow, travelling at five or six miles per hour, and were used primarily as a cheap way to transport coals. Furthermore, the general public was opposed to this new form of transportation. When a new railway between Newcastle and Carlisle was approved in 1829, it was on the condition that horses, not locomotives, should be used[11].

At the time, an alternative to locomotives was stationary steam engines that used cables to haul loads along the railway. This was the preferred method for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR) that the Stephensons were working out. However, Robert strongly believed that locomotives were in their infancy and had significant potential for improvement. It was against this backdrop that the directors of the L&MR proposed the Rainhill trial to determine whether locomotives had a future on their line[12]. As we saw, Robert Stephenson’s “The Rocket” would go on to win the competition. The L&MR directors were so satisfied with the performance that they decided only locomotives would be used on their railway, the first railway in the world to do so. Eleven months after the Rainhill trial, L&MR was officially opened.

As soon as the L&MR was completed, Robert Stephenson moved on to the next project, the London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR). There, he faced further opposition against the railway. The aristocrats despised the interruptions on their land; the working class feared for their industrial interests; and the residents of market towns built on turnpike roads lamented the loss of business[13]. So strong was the resistance that while Robert completed the first survey for L&BR in 1830, it wasn’t until 1833 that both the House of Commons and the House of Lords gave their approval[14]. The ordeal cost the company £73,000 (more than £7 million today) just to obtain the Act of Incorporation[15]. Over the next four years, 20,000 labourers worked on the L&BR. One engineer compared building the railway to the Great Pyramid of Giza[16]. While the final cost of £5.5 million was more than double the original budget[17], the L&BR was officially opened in September 1838, whereupon passengers could travel between London and Birmingham in 5 1/2 hours[18].

With the success of the L&BR, the Railway Revolution truly started, and in a few short years, scepticism turned into a mania. In 1845 alone, Parliament passed bills for 120 new lines, measuring 2,883 miles and with a budgeted cost of £44 million[19]. Aristocrats, who were vocal opponents of the railway, became big supporters as they saw opportunities to line their pockets when the railways passed through their land. In one instance, a nobleman with an estate valued at £30,000 was paid £60,000 when two railway lines passed through his land[20]. By 1850, the mania had cooled down, but unlike most speculative bubbles, this one left a positive legacy of 6,000 miles of paved railways[21].

George Stephenson died in 1848 at the age of sixty-seven from pleurisy[22]. For Robert, his father’s passing, six years after his own wife died, was a heavy blow. A life of hard work also took its toll, and Robert’s health deteriorated. In September 1859, Robert fell seriously ill on a trip to Norway. With the help of his friends, he made it back to England but died a month later, on 12th October 1859. In the final decade of his life, Robert served as a Member of Parliament, the President of the Institution of Civil Engineers, and a Fellow of the Royal Society[23]. As a testament to his character, Robert became a loyal friend of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, his main engineering rival.

Over three generations, the Stephensons went from poverty to affluence, from illiteracy to becoming a Member of Parliament, from living in a small village to a globetrotter. When George Stephenson married Fanny, it was said that he bettered himself because Fanny, through years of loyal service, had saved a few gold pieces[24]. Nevertheless, even with this small amount of money, when the Stephensons moved to Killingworth, George had to enlarge the family cottage with his own hands[25]. The death of Robert’s younger sister, at the age of three weeks old, was also a reminder of the shockingly high rate of infant mortality at the time. While the rapid ascent of the Stephensons was not experienced by everyone in Britain, a significant number of people did see their living standards improve. Between 1800 and 1900, the average inflation-adjusted income in Britain more than doubled, and in the subsequent 100 years, it quintupled[26]. Over the past two centuries, the percentage of the British population living in poverty declined from over 40% to less than 5%[27].

Global Progress

Broad-based progress began in Western Europe and then gradually spread across the world[28]. This diffusion hasn’t been smooth and hasn’t yet reached all corners of the world. Nevertheless, the past two centuries saw citizens in many countries getting richer, healthier, and more educated. What’s remarkable, though, is that broadly shared improvements in living standards are a recent phenomenon and have been virtually absent from human history until only a few generations ago. As Vaclav Smil wrote in his book Growth: From Microorganisms to Megacities, “nearly all fundamental variables of premodern life - be they population totals, town sizes, longevity and literary, animal herds, households potions and capacities of commonly used machines - grew at such slow rates that their progress was evident only in very long-term perspectives. Moreover, often they were either completely stagnant or fluctuated erratically around dismal means, experiencing long spells of frequent regressions.”[29]

Take health as an example. At the peak of the Roman Empire, the life expectancy at birth for its inhabitants was around 25 years. Even this might be optimistic as the life expectancy of slaves and the high mortality of Roman soldiers were not considered[30]. In any case, a life expectancy of 25 years was no better than what people in hunter-gatherer societies achieved[31]. By the 18th Century, the global life expectancy at birth was still below 30 years[32].

Why was there no noticeable improvement in life expectancy for such a long period of human history? For one, the living conditions for many people were unhygienic, especially in urban areas. In 18th Century Edinburgh, pedestrians would run for cover upon hearing the shouts of “Gardyloo”, which forewarned that the residents of upper-floor tenement buildings were about to empty their chamber pot out of the window. In Copenhagen, basins were dug under people’s houses to collect wastewater. Those basins often leaked into nearby soil, which contained wooden pipes that carried drinking water into the city[33]. In those conditions, it is unsurprising that diseases spread quickly. We associate the plague with the Black Death of the 14th Century, but plague outbreaks were common in Europe for centuries afterwards. In Copenhagen, a plague outbreak in the early 18th Century killed 20,000 of the city’s 66,000 residents. That turned out to be Copenhagen’s last major plague outbreak, but other epidemics continued ravaging the city. In 1853, a cholera outbreak killed just under 4% of the city’s 130,000 residents[34].

The primitive state of medicine was another contributor to poor life expectancy. Based on a limited and often faulty understanding of human biology, many early medical interventions did more harm than good. Until the 18th and 19th Centuries, the dominant theories for the causes of diseases among the medical communities in Europe were humorism, a belief that illnesses were caused by an imbalance of bodily fluids consisting of blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile, and the miasma theory, which argued that diseases were caused by bad odour and atmospheric disturbances. While one could see some rudimentary logic behind those theories, they didn’t get to the underlying causes of diseases and often led to practices that were barbaric, such as bloodletting, or ineffective, such as burning sulphur and juniper berries in the streets. In addition, medicines that we take for granted today, like anaesthetics and antibiotics, were unavailable one or two centuries ago, meaning common surgeries and wounds could be fatal.

Perhaps the most important explanation for poor health was simply the dire poverty that the vast majority of people had to contend with. At the start of the 19th Century, 80% of the global population had to survive on an income of less than $1.90 per day, inflation-adjusted to 2011 prices, and 95% had an income of less than $5 per day[35]. With that level of income, almost all spending went to the basic necessities of life. In 1688, 90% of private consumption in England and Wales went to food, housing, and clothing[36]. Even that was insufficient for a decent life. According to research by the OECD, in 1820, three-quarters of the world population “could not afford a tiny space to live, food that would not induce malnutrition, and some minimum heating capacity.”[37] When one could barely afford basic nourishment and the prospect of famine and hunger was never far away, it’s unsurprising that health suffered.

The fact that poverty was the default condition for so many people deserves more of our attention. As Charles Dickens painted starkly in A Tale of Two Cities, a historical novel set in the time of the French Revolution, “As to the men and women, their choice on earth was stated in the prospect - Life on the lowest terms that could sustain it… or captivity and Death in the dominant prison on the crag.”[38] The reason that such a dire prospect had persisted for so long is that economic growth was excruciatingly slow.

Estimates of the size of the global economy from a few centuries or millennia ago contain significant uncertainties, but most findings pointed to a level of growth that was barely noticeable. Angus Maddison estimated that per capita income on the Italian Peninsula doubled between 300 BC and 14 AD[39]. This sounded impressive, and indeed, it was for that era, but this translated to an annual growth rate of only 0.2%. Furthermore, this growth came from the plunders, tributes, and taxes the Romans collected from their conquered territories. During the same period, per capita income in areas that contain modern-day Greece, Turkey, Egypt, Tunisia, and Spain barely changed. From 300 BC to 14 AD, the per capita income of the entire Roman Empire grew by only 20%, or 0.06% per year. By 1000 AD, when the Western Roman Empire had disintegrated, per capita income on the Italian Peninsula returned to the level of 300 BC[40]. The population also declined. Over the span of 1300 years, the area that contained the most advanced civilisation of its time outside of China saw no economic growth on a per capita or aggregated basis.

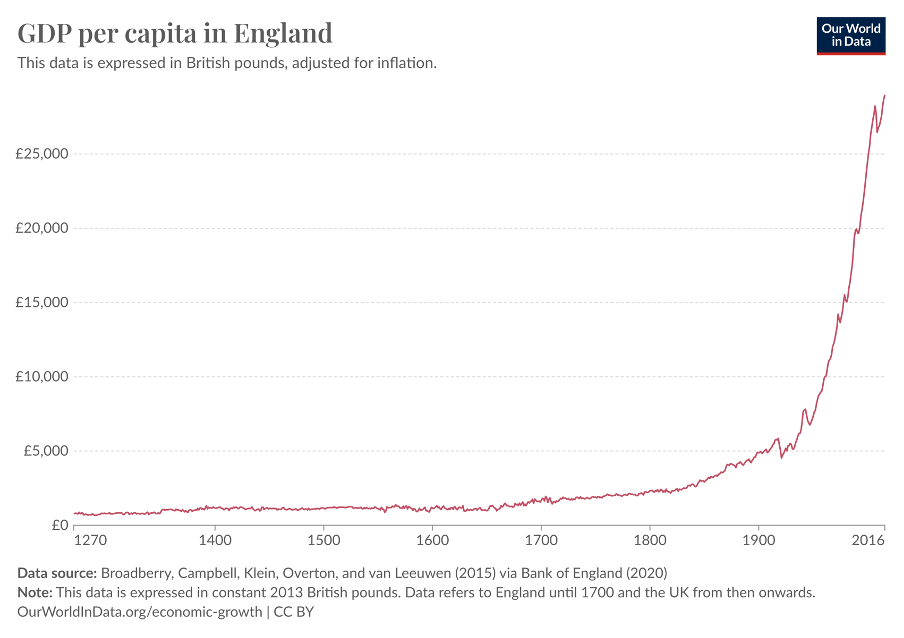

By the late Middle Ages, the quality of economic data had become more robust. In England, per capita GDP was around £800 at the start of the 14th Century. It increased to £1,200 at the beginning of the 15th Century after the plague reduced the size of the English population by almost half. It then remained at this level for the next 250 years[41].

To make things worse for the average person, whatever little economic growth that existed was often appropriated by the ruling elites through a repressive and extractive system. Before the French Revolution, the nobility and the clergy were exempt from taxation, while the rest of the citizens had to pay different taxes[42]. The most famous and hated was the gabelle, or the salt tax, which forced citizens to purchase a minimum amount of salt from the state monopoly whether they wanted it or not. Failing to make the minimum purchase could result in imprisonment and, if repeated, death[43]. Amazingly, with a few brief lapses, the salt tax existed from the 13th Century until 1946.

Today, we often associate innovation with prosperity, but in feudal societies, new technologies often enabled the elites to cement their power. In Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson described how monasteries in Medieval Europe used watermills to extract more money from the general population. For example, in the 13th Century, the Monastery of Saint Albans in Hertfordshire spent £100 upgrading its mills and then insisted that tenants bring all their corn and clothes to the mills for processing. When the tenants refused and washed their clothes by hand, the abbots attempted to confiscate the tenants’ clothes by force. The tenants protested to the King, who, unsurprisingly, sided with the abbots. The tenants had to bring their clothes to the mills and pay the fees set by the monastery[44].

The prevalence of poverty had wider ramifications beyond health. For one, education was not widely available. At the start of the 19th Century, less than 20% of the global population had some form of basic education, and just over 10% were literate[45]. In many places, the ruling elites had little incentive to provide education for the general population. They preferred to lavish their wealth on themselves and worried that an educated population would challenge their grip on power. The religious institutions did establish some schools and universities, but places were limited, and their purpose was to train future clergy. In China, the emperors required educated officials to coordinate their large empire, which gave rise to a merit-based imperial examination system. However, those who could afford years of tutoring mostly came from a small number of wealthy landowners and merchants.

The lack of centrally funded education systems and the fact that people spent all their income on subsistence meant that education was simply not an option for most people. In addition, the precarious nature of existence pushed many children into labour. Children as young as six were expected to help with farm work or domestic chores[46]. As they grew older, they moved on to more demanding jobs. The Industrial Revolution was notorious for child labour, but that was sadly a continuation of practices long rooted in history. This didn’t diminish the gruesome realities for many children in the 19th Century. In England in the 1850s, more than a third of boys and one-fifth of girls aged between 10 and 14 were working[47]. Children made up 20-50% of the workforce in mines, working shifts as long as 12 hours for a fraction of the adult pay[48]. Charles Dickens, whose novel Oliver Twist portrayed children's life during the Industrial Revolution, worked in a factory when he was 11. For a year, Dickens worked 10 hours a day, 6 days a week, to pay off his father’s debt[49].

The poor standards of living for the majority of people in history contrasted starkly with the lavish lifestyles enjoyed by some. The pyramids of Egypt, the Palace of Versailles, and the Forbidden City of Beijing are testaments of the riches that were amassed by the elites. This points to another feature of societies centuries and millennia ago: inequality was as great as, if not greater than, what we have today. While we do not have detailed statistics about the distribution of income and wealth from Antiquity, we can get a sense of the scale of inequality. During the reign of Emperor Nero, six men were said to own about half of the Roman province in Africa[50]. As Martin Wolf wrote in The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, “The degree of inequality frequently reached the limit set by the need to leave the labouring poor with a subsistence income.”[51] From Medieval Europe, we begin to get some quantitative measures of inequality. Guido Alfani’s book, As Gods Among Men: A History of the Rich in the West, is a useful reference. At the beginning of the 14th Century, the top 1 percent in the Florentine state owned 29% of the overall wealth, and the top 5% owned 55%. In Scotland in 1770, the top 1 percent owned 27% of the real estate. At around the same time, Sweden’s top 1 percent owned 43% of the wealth, a comparable level to England, while the top 1 percent in Finland owned a staggering 63% of the overall wealth[52]. For context, the top 1 percent in America currently owns 30% of the overall wealth[53].

The lack of human progress, at least for the average person, from the dawn of agriculture until the Middle Ages prompted some people to suggest that humanity will forever be trapped in this sorry state of affairs. The English clergyman and economist Thomas Robert Malthus argued that because the growth in human population tends to outstrip the increase in agricultural productivity, famine, pestilence, or epidemics would inevitably set back progress. “The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race.”[54] Malthus’ argument that human population growth is the seed for future catastrophe, popularly known as the Malthusian Trap, has influenced many thinkers and conservationists. However, as Malthus penned his famous essay in 1798, things were changing around him.

Since 1000 AD, the global population has increased by 25-fold, income per capita has grown by around 20-fold, and the global GDP has increased by 500-fold[55]. Most of this growth occurred in the past two hundred years, from the time of Malthus to the present day. Over the past two centuries, the global per capita income grew by 12-fold, compared to a growth of just 50% over the preceding eight centuries[56]. The period of rapid economic growth began in Europe. Between 1660 and 1800, per capita income in England doubled. It doubled again from 1800 to 1900, and between 1900 and 2000, despite the impacts of two world wars, per capita income increased by five-fold[57]. Similar growth rates were experienced in other European countries, including the Netherlands, France, and Spain. In the second half of the 20th Century, with a few exceptions, sustained economic growth became a global phenomenon.

As the world became richer, life for the average person improved dramatically. The percentage of the global population living in poverty declined from 80% in 1820 to 10% today[58]. In absolute terms, the number of people living above poverty increased by more than 50-fold, from 120 million to 6.6 billion over the past two hundred years[59]. In 1688, people in England and Wales spent 90% of their private expenditures on food, housing, and clothing. In 2001, that proportion fell to 36%[60]. This enabled spending on education, health, recreation, and entertainment to increase from 3.5% to 29% of private expenditure over the same period[61].

The comfort and convenience of modern life would be unrecognisable for our relatives a few generations back. Three-quarters of the world’s population now has access to safe drinking water on-premises (close to 100% in North America and Europe)[62]. Electricity, accessible to 90% of the world’s population[63], has transformed many aspects of our lives. Electric lights have allowed people to stay up, socialise, or study past sunset. Modern appliances such as refrigerators, air conditioning, washing machines, and microwaves have greatly reduced the burden of household work. The time spent on cooking and laundry halved in the US from the 1920s to the 2000s[64]. Most forms of entertainment and communication, including TVs, the internet, and mobile phones, simply didn’t exist at the start of the 20th century.

Health outcomes have improved, too. Since 1800, the global average life expectancy at birth has more than doubled from around 30 years to more than 70 years[65]. Furthermore, even the country with the lowest life expectancy today outperforms the best country from 1800[66]. Lowering childhood mortality played an important role - the chance of a newborn surviving to their fifth birthday has increased from roughly 50:50 in 1800 to 95% today[67] - but life expectancy has increased across all age groups.

Higher spending on healthcare undoubtedly helped, but other developments have also contributed to the increase in life expectancy. First, we have considerably increased food supply so that more people can access a diet with sufficient calories and nutrients to promote healthy growth and support a well-functioning immune system. Contrary to Malthus’ prediction, we have increased food production faster than population growth. Second, we have made significant progress in reducing the burden of infectious diseases. This is partly due to better sanitation and hygiene, but also due to advances in science and technology, in particular antibiotics and vaccines. The eradication of smallpox alone is estimated to have saved 5 million lives per year[68]. Third, we have started making progress on non-communicable diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Diuretics, which lower blood pressure, and statins, which reduce cholesterol, have helped to extend the lives of millions of people. Between 1990 and 2013, the age-standardised death rate from non-communicable diseases declined by 19%[69].

Education attainments have followed a similarly positive trajectory. Between 1820 and today, the percentage of adults who are literate globally has increased from less than 15% to over 85%[70]. Today, roughly 90% of children of primary school age are enrolled in school, compared to less than 5% in 1820[71]. In 1870, the typical adult had less than 1 year of schooling, compared to 9 years today[72]. Over the past one hundred years, governments around the world have significantly increased their commitment to education. At the start of the 20th Century, The British and French governments spent 1% of the GDP on education. Today, they spend 5% of GDP on education, and the global average is 4%[73].

One potentially unexpected area of progress is the reduction in the frequency of violence over the long term. This might feel unlikely given the two World Wars and a range of other conflicts in the 20th Century, but statistics demonstrate that the chance of meeting a violent end is much lower today than in the past. Steven Pinker’s book Better Angels of Our Nature showed that the annual homicide rates in pre-state societies were typically in the range of hundreds of deaths per 100,000 people[74]. By the time of Medieval Europe, it fell to double digits. Today, it’s in the single digits. In most Western European countries, the annual homicide rates are below 1 per 100,000[75]. Contrary to popular media reports, the frequency of violent crimes in large cities has reduced in recent decades. For instance, the number of murders in New York has declined from roughly 2,000 murders per year in the 1980s[76] to about 400 today[77].

Statistics offer one way to examine violence. Another is to think about our attitude towards it. For many years, my commute in Edinburgh took me past a small plaque on the Royal Mile. Most tourists walked past it without noticing it, but inscribed on it was the date of the last public execution in Edinburgh: 21st June 1864. Less than two hundred years ago, public executions were practised across Europe, and crowds, including children, would gather to see them. Many of the practices that were accepted and celebrated not long ago, today, we would find them absolutely abhorrent. When the guillotine was introduced, it was considered moral progress because it replaced much more barbaric practices such as burning at the stake, quartering, or leaving the victims to starve and rot in cages[78].

Rewind the clock further, an estimated two million men, women, and children died during the Middle Passage of the Transatlantic Slave Trade[79]. Those who survived the journey suffered intolerably upon their arrival. In Medieval Europe, witch hunts claimed 40,000 - 50,000 innocent lives[80]. When empires and states went to war, there were no international agreements that protected civilians or captives. Most of the time, they met a sad and frightening end. The Romans brought their captives to the Colosseum to fight to the death, get mauled by wild animals, or enact plays with human sacrifices. Half a million people died in the amphitheatre to provide entertainment for the Romans[81]. Out of all the progress in recent centuries, our changing attitude towards violence is perhaps the most encouraging, for this didn’t come from a technological solution but was born out of our growing respect for each other’s well-being.

Before we end the section on Progress, there are two final points to discuss. First, one important critique of global progress is that it has been uneven. This is true. If we divide the world into the West and the Rest, in 1000 AD, there was no difference in per capita income between the two blocks, but by 2000, the gap had increased to 6:1, favouring the West[82]. Other inequalities also widened, including life expectancy and education attainments. However, it’s important to recognise that the world had been more equal because all countries were poor. Furthermore, while inequality between countries was low, inequality within countries was incredibly high. An enormous gap existed between the luxurious lifestyle of the elites and subsistence living that the rest had to contend with. Over the past millennium, some countries have become richer, and others have become a lot richer, but citizens of most countries can claim living standards that are significantly better than that of their relatives a few generations back. Of course, this doesn’t mean that the path of development has been fair. Colonialism and the Slave Trade were gross injustices and abuses of human rights. One of our goals for the coming decades is to ensure that progress is compatible with our respect for human rights and that the benefits are broadly shared.

The second point is a modification to the argument that progress was limited until the recent two centuries. Yes, the living standards for the average person had barely changed until the 19th Century, but one thing that did change was the size of the human population, which grew 80-fold from 4 million in 10,000 BC to 320 million in 1800[83]. Oded Galor argued in The Journey of Humanity and the Key to Human Progress that the ability to sustain larger populations should be viewed as progress in itself. Larger, and importantly, denser, populations “were more likely to generate both a greater demand for new goods, tools and practices, as well as exceptional individuals capable of inventing them. Moreover, sizeable societies benefited from more extensive specialisation and expertise, and greater exchange of ideas through trade, further accelerating the spread and penetration of new technologies.”[84] Galor went on to suggest that this positive feedback loop of technological advances supporting larger populations, which in turn generated more innovations and technologies to support even larger populations, might be the underlying force that enabled humanity to escape the Malthusian Trap. Population growth is a controversial topic that we will discuss another time, but in the context of progress, it’s worth considering that more people might be better than fewer.

Emergence of Capitalism

There is a rich discourse on the history of capitalism. They are important because how we define capitalism affects our perception of it. Were the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and English East India Company (EIC) capitalistic organisations? They certainly shared features of modern-day enterprises, such as limited liability and common stocks held by investors. They were driven by profits and paid dividends to their stockholders. They even faced the same principle-agent problems - where the interests of the business owners and managers diverge - that still plague today’s businesses. Yet, they also held extraordinary power that few would consider legitimate today, notably the ability to raise an army and administer entire countries. They carried out activities that would shock most modern business leaders, such as waging wars and killing and enslaving civilians.

As we will see, the boundary of what counts as capitalism and what doesn’t is blurred. There was no Big Bang moment where people woke up one day and decided to practise capitalism. Rather, capitalism emerged gradually as people searched for ways to improve on previous systems and institutions. Capitalism is also not a monolithic concept. When a competitive market is paired with democratic political institutions, we have democratic capitalism. When state-owned enterprises control a significant part of the economy, we have state capitalism. When capitalists can enrich themselves by shaping politics and regulations in their favour, we have crony capitalism. Each form of capitalism has its virtues and limitations, with some forms decidedly more virtuous than others. As ideology goes, capitalism is far more fluid and adaptable than many other ideologies. Those characteristics are worth acknowledging as they caution us from embracing capitalism unconditionally or rejecting it dogmatically. A more productive approach is to view capitalism as one way of organising our political economy, with some clear advantages but also significant scope for improvements.

In the Late Middle Ages, Italian states, in particular Venice, began to grow rich from trading in the Mediterranean. Venice’s favourable location made it a crucial node along the important trade routes with Asia and North Africa. Trading created a new class of wealthy merchants. Interestingly, the public didn’t applaud their commercial acumen but treated the merchants with contempt. This wasn’t necessarily because of inequality, for feudal societies were used to enormous disparities in wealth between the rich and the poor, but because feudal societies were extremely rigid and hierarchical. The idea that commoners could become rich upset the social order. In an attempt to hold on to their status, the nobility and the clergy painted enrichment through commercial activities as sinful and unwarranted, and the public went along with it[85].

To maintain the social hierarchy, sumptuary laws dictated what people could consume. The nobility was entitled to more luxuries than commoners. Successful merchants, because they were officially commoners, were not permitted to have the same lifestyle as the nobles, even if they could afford it. Guido Alfani wrote, “Across Europe, sumptuary laws imposed limits not only on the precious items one could own and display, but also on the amount which could be spent in organizing events or on specific occasions, like marriages or baptisms. In the case of baptisms, for example, across Europe sumptuary laws defined whether it was allowed to throw a party at home after the event and, in such a case, how many guests could be invited, what food could be served and in what quantity; the acceptable value of the gifts offered by the godparents; the maximum number of participants at the procession carrying the newborn to church and how they should be dressed; and so on.”[86]

Given the rigid hierarchy, it might not be a surprise that the initial success of the Italian states eventually ran out of steam. Some wealthy merchants managed to integrate themselves into the upper class through marriages or purchasing titles, upon which they became equally zealous in defending their positions as the old nobility. Other merchants, however, couldn’t resist the social pressure and chose to donate all their worldly possessions and search for a quiet life of contemplation. Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, who was born into a family of rich silk merchants at the end of the 12th Century, renounced his inheritance, begged for stones to restore ruined chapels, and eventually became St Francis, the founder of the Franciscan Order[87].

By the 15th and 16th Centuries, the centre of European maritime trade shifted to the Iberian Peninsula. Advances in ship designs made longer voyages possible. The Spanish and Portuguese traders explored the Atlantic islands and the African coast and eventually reached the Americas and Asia, kicking off the era of European colonialism. Spain captured large parts of the Americas, and Portugal claimed Brazil and established several trading ports in Asia. Colonisation brought a huge inflow of resources into Europe. Angus Maddison estimated that 1,700 tons of gold and 73,000 tons of silver were plundered from the Americas to Europe, which would be worth $175 billion at today’s price [88].

The inflow of gold and silver failed to kick-start sustained economic growth on the Iberian Peninsula. Between 1500 and 1700, Spanish per capita GDP was flat. Most of the plundered gold and silver went to finance a series of destructive wars by the Spanish monarchy in an attempt to create hegemony in Europe. This included the Eighty Years’ War against the Dutch and Spain’s attempt to invade England in 1588. Those wars were costly, with Spain defaulting on its public debt multiple times in the 16th Century[89].

By the 17th and 18th Centuries, England and the Netherlands became the leading European maritime powers. English and Dutch inventors also made significant contributions towards improved charting and navigation. In time, they dislodged Portuguese traders from large parts of Asia and challenged Spain’s control in the Americas, especially in the Caribbeans and North America. Between 1500 and 1800, the Dutch VOC accounted for 45% of the European voyages to Asia[90]. Over the company's lifetime, it constructed 1,500 ships and sent nearly a million sailors, soldiers, and administrators to its ports in Asia[91].

It’s impossible to do justice in a few pages, but it would be irresponsible not to discuss the impact of European colonialism on the rest of the world. The European colonisation of the Americas was catastrophic for the native inhabitants and marked one of the darkest chapters of human history. The Spanish strategy of imperial conquest was particularly barbaric. It consisted of capturing and killing the local elites, enslaving the remaining inhabitants, and sending resources back to Spain. In 1532, Francisco Pizarro led a Spanish expedition into Peru. Despite an enormous disparity in numbers, Pizarro’s army defeated the Inca army and captured Emperor Atahualpa. Atahualpa promised and delivered 85 cubic metres of gold and twice the volume of silver as a ransom, but Pizarro went on to execute him anyway, putting an end to the Inca Empire[92]. For the remaining inhabitants, the Spanish colonisers used extractive institutions to obtain forced labour. A head tax was levied on adults, and goods were forcibly distributed to the local people at prices determined by the colonisers[93]. Through violence and diseases, two-thirds of the native population perished[94].

In North America, the population density was lower, and there was no centralised political system that the colonisers could hijack. Nevertheless, the eventual fate of the native inhabitants was similar to those in the South. They were pushed off their land, and a significant number perished. The European Colonisation of the Americas also saw millions of slaves shipped from Africa to work on plantations. Millions of people died during their voyage, while those who survived were made to toil under gruesome conditions.

The impact of Europeans on Asia was more nuanced. Early interactions were focused on establishing trades on more or less commercial terms. In fact, a third of the gold and silver that Europeans took from the Americas went to pay for goods from Asia[95]. Beyond establishing trading ports, sovereign integrity was generally respected. Why were European actions much more restrained in Asia? In 1500, per capita income in Western Europe was only 35% higher than in Asia. In addition, India’s economy was bigger than that of the entire Western Europe in 1700, and China’s economy was bigger than Western Europe in 1820[96]. In comparison, when the Europeans reached the Americas, Western Europe’s economy was five times larger than that of the Americas[97]. Europeans were more restrained in Asia because societies there were more capable of putting up a fight.

As time went by and the economic performance of Western Europe pulled ahead of Asia, European colonisers became more dominating. The Dutch colonisers were particularly aggressive. Upon realising the potential of the Asian trade, the Dutch set up the VOC in 1602 with a monopoly charter to trade in Asia. The following year, with the approval of Prince Jayawikarta, VOC established a trading post in West Java. However, the tension between the Dutch and Prince Jayawikarta began to increase. In 1619, a Dutch force led by Governor Jan Pieterszoon Coen razed the city of Jaykarta and established Batavia, the Dutch headquarters in the East Indies. At that time, the world’s entire supply of nutmeg and mace came from a small island called Banda Island, which made the trade extremely profitable. Coen wanted to monopolise this trade for the Dutch, so in 1621, he set sail for Banda Island. The island’s 15,000 residents were no match against the Dutch invaders, and Coen was able to conquer the island easily. That, sadly, was not the end of the story. Possibly because he feared that the island’s residents would escape and grow nutmeg elsewhere, Coen began slaughtering the local residents. By the end, only 1,000 island residents survived, whom Coen enslaved on his nutmeg plantations. The massacre of the Bandanese marked the start of the Dutch effort to turn the East Indies into a plantation colony[98].

Queen Elizabeth granted the East India Company the charter to trade with the East Indies on the last day of 1600. For the first one hundred years, the EIC fought with other European trading companies for a foothold in Asia. Although it managed to dislodge Spanish and Portuguese traders, the Dutch’s stronghold on the East Indies proved too difficult to overcome. As a result, the EIC focused on trading with India. The British initially had a cordial relationship with the Mughal Empire, whose control and military power were too great to be challenged. In the 18th Century, the Mughal Empire began to collapse, and the EIC took the opportunity to take administrative control over much of India. While far from being bloodless, the EIC was more humane than its Dutch counterpart in the East Indies. There were even some progressive voices in the EIC administration. The liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill was an EIC administrator for 35 years, and Jeremy Bentham was consulted on the reform of Indian institutions[99]. Nevertheless, the EIC was still an extractive institution whose purpose was to further British interests, not those of India. 5% of India’s national income went to British personnel, and many industrial policies, such as favouring British textile export to India over developing a domestic textile industry, worked against the Indian economy[100].

The EIC’s impact on China was decidedly negative. In the 1770s, to reduce the trade deficit with China, the EIC started growing opium in Bengal to finance the imports of Chinese goods such as tea and porcelain[101]. This caused a series of opioid epidemics in China. Despite the Chinese government banning the opium trade, the EIC carried on. In 1839, the Qing Emperor sent his officials to enforce the opium ban[102]. Viceroy Lin Zexu wrote a letter appealing to Queen Victoria to end the opium trade. This produced no response, so Lin confiscated and publicly destroyed over 2 million pounds of opium. In retaliation, the British Navy invaded China, ultimately leading to China ceding Hong Kong to Britain and an indemnity of 21 million silver dollars. China’s defeat to the British in the Opium War opened the country to European imperial conquests over the following century.

The impact of European Colonialism in Africa went beyond the Slave Trade. By 1913, European powers controlled most of Africa, with only Liberia and Ethiopia maintaining their full sovereignty. The Europeans established extractive institutions to control Africa’s resources and productive sectors. For example, Leopold II of Belgium laid claim to the Congo Free State and proceeded to extract ivory, rubber, and other resources with forced labour from the native inhabitants. Those who didn’t meet the rubber quota, which was often unrealistic, were executed, with their hands chopped off as proof of the execution. Forced mutilations were common as soldiers could shorten their service by bringing more hands. Objective data is difficult to obtain, but it has been estimated that 5[103] to 20[104] million people died in less than three decades. After decolonisation, many of the extractive institutions remained and hindered the economic development of African nations.

As suggested earlier, European mercantilism had some features of capitalism, but there were also important differences. Early mercantile activities were heavily influenced by the economic theory of bullionism, which saw wealth as the accumulation of precious metals. The goal of mercantilism was to increase a nation’s trade surplus by exporting more goods than one imports. Commercial activities were viewed as a zero-sum game, where one person’s gain must come at someone else's expense. This view was clearly articulated by The Discourse of the Common Weal of this Realm of England, published in 1549, which stated, "We must always take heed that we buy no more from strangers than we sell them, for so should we impoverish ourselves and enrich them.”[105]

In addition, European merchants were traders. Their main source of profits came from arbitraging the price differences of goods between distant lands. William Magnuson’s book For Profit: A History of Corporations documented that the EIC were able to purchase ten pounds of nutmeg in the Banda Islands for less than half a penny and sell them for £1.60 in England[106]. Aside from running plantations using slave labour to produce agricultural commodities, the European trading companies did very little in terms of production.

Another vital difference comes from Europe’s political structure at the time. Most countries had absolutist regimes, where power was concentrated in the hands of the monarchs and aristocrats. They were able to appropriate most of the economic gains from trading, meaning that the average European inhabitants experienced little benefit. In Spain, the monarchy waged destructive wars, which were counterproductive to any kind of economic development. The elites’ hold on power was also a barrier to innovation, so the inflow of resources was unable to catalyse sustained economic growth through productivity gains. This was a classic case of the Resource Trap, which still plagues some countries today. Due to those differences, I view European mercantilism as distinct from modern capitalism.

The transition from European mercantilism to capitalism required changes to social and political systems. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson convincingly argued that inclusive political and economic institutions were vital in generating sustained economic growth. They traced the emergence of those inclusive institutions to England and Northern Europe. The Black Death in the 14th Century reduced the English population by half, creating a labour shortage and demands from peasants for higher pay and better working conditions. The landlords resisted, and the English Parliament passed the Statute of Labourers, which capped wages and limited the movement of peasants to prevent them from finding better working conditions. This led to the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381. While the revolt was eventually suppressed, it ended the enforcement of the Statute of Labourers and resulted in the decline of serfdom in England[107].

The Peasants’ Revolt created another feature that Ellen Meiksins Wood argued contributed to the emergence of capitalism. Because the aristocracy’s relatively weak coercive power was made apparent, landlords had to find an alternative way to increase their income than simply using brute force. This solution was a system of tenant farming where landlords leased their land to the highest bidder. This created incentives and pressure for tenant farmers to adopt new technologies and practices that increased yield. The practice of investing in new agriculture technologies to boost productivity, with the subsequent increase in output reinvested back in leasing more land and increasing scale, had a clear resemblance to capitalism[108].

In the Late 15th and 16th Centuries, while the Spanish monarchy “benefited” from the inflow of gold and silver from the Americas, the English monarchy had to rely on domestic taxation. This gave greater representation to merchant interest[109]. The path towards inclusive institutions was not guaranteed to succeed. The English monarchy attempted several times to revert to absolutism and sideline the parliament. The crucial moment was the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when the parliament invited William of Orange to depose James II and rule as a constitutional monarch. From that point onwards, the English Parliament obtained sufficient power to prevent any attempt to revert to absolutism[110].

An important benefit of inclusive institutions was that the barriers to innovation were reduced. Previously, inventors had to petition the monarchs. This process ensured that any subsequent development would work out favourably for the monarchy and not challenge its power. In 1589, when William Lee brought his stocking frame knitting machine to Queen Elizabeth, she refused him a patent, responding, “Thou aimest high, Master Lee. Consider thou what the invention could do to my poor subjects. It would assuredly bring to them ruin by depriving them of employment, thus making them beggars.”[111] In contrast, when Richard Arkwright invented his spinning frame in 1769, he was able to receive a patent and set up a factory. In the following decades, the English textile industry boomed and became the driving force for the Industrial Revolution. As Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson wrote, “The fear of creative destruction is the main reason why there was no sustained increase in living standards between the Neolithic and Industrial revolutions.”[112] And as Joseph Schumpeter argued in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, “This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism.”[113]

Beyond the emergence of inclusive institutions, another crucial ingredient of capitalism was the Enlightenment. The adoption of the printing press in Europe greatly reduced the cost of books. Before the printing press, a manuscript typically cost more than two months of wages, which was prohibitively expensive when 90% of personal expenditures went on necessities. By the 17th Century, the cost of books had fallen to below a day’s wages[114]. Lower printing costs also made it more economical for publishers to take a chance on less proven ideas. It turned out that the biggest enemy of superstitions and dogma was a flood of new ideas.

Rational thought was crucial to scientific advances and technological progress. Rational thinking led us to reject the notion that the Sun revolves around the Earth and replaced it with a heliocentric view. This made possible the discovery of gravity and other fundamental forces. New understandings of the laws of physics contributed to advancements in engineering, fuelling a wide range of breakthroughs and innovations. Similarly, new knowledge about chemistry and biology helped the medical community to adopt the germ theory of disease, without which accurate diagnoses and treatments for diseases would be impossible.

The combination of rational thought and inclusive institutions was powerful. Rational thoughts increased the supply of ideas and innovations, and inclusive institutions reduced the barriers to their adoption. Together, they kicked started a virtuous economic process. Innovations increased productivity, creating higher profits that were reinvested in purchasing more machinery and financing new research. As the stock of physical capital per worker increased, labour output increased. When wages rose, education became more affordable, which enhanced human capital and complemented the increase in physical capital. Between 1820 and 2003, the stock of machinery and equipment per capita increased by 155-fold in the U.K., and the average years of education increased by 8-fold. Hours worked per person decreased by 40%, but per capita GDP still rose by 10-fold[115].

A final ingredient that was necessary for sustained economic growth and modern-day capitalism was abundant energy. All those machinery and equipment required a source of energy to power them. Between 1820 and 2003, the per capita energy consumption in the UK increased by six-fold[116]. Watermills and windmills were important in the early phases of the Industrial Revolution, but they had limits. The extraction of coal, followed by oil and gas, was crucial for powering economic growth. Fossil fuels obviously came with significant environmental costs, but the social and economic progress of the past two hundred years would have been impossible without them.

Energy and mechanisation facilitated advancements in transportation. This happened in four phases: Shipping, Railway, Automotives, and Aviation. Advances in transportation increased personal mobility, which helped to spread ideas, and importantly, they reduced the cost of long-distance trade and expanded the size of markets. Advances in transportation enabled globalisation, another crucial feature of modern capitalism. While globalisation has come under a lot of attacks recently - mostly unfairly - it has been enormously beneficial for economic growth. As David Ricardo and Adam Smith argued long ago, global trade enables countries to specialise in industries where they have a competitive advantage, increase their productivity and outputs, and improve national welfare. As the world faces urgent and common challenges, the benefits of globalisation are worth remembering.

At this stage, our analysis of the history of capitalism and economic progress follows a conventional line that focuses on institutions, enlightenment, and energy. However, there’s one additional consideration. Even with the virtuous cycle of productivity gains and economic growth, there was no guarantee that the average person would benefit. The increasing labour output and profits could have been appropriated by the business owners, leaving wages for workers largely unchanged. Indeed, the early stages of the British Industrial Revolution were notorious for the poor working conditions. In the US, inequality rose sharply during the Gilded Age[117]. The exploitation of labourers by landlords could have simply been replaced by the exploitation of labourers by capitalists. After all, this was Marx’s critique.

What made the capitalists share the profits with workers? Did they do it out of the goodness of their hearts, was it out of their self-interest, or did other intervening forces play a role? As it turned out, it was a combination of all three.

In 1885, William Lever and brother James started a business manufacturing and selling soap. Through innovative marketing, Lever Bros. quickly became a commercial success. By 1888, the company was making 3000 tons of soap per week[118]. The Lever brothers wanted their company to be more than just profitable, they also wanted to improve the livelihoods of their workers. The company constructed Port Sunlight, a modern company town where workers received subsidised housing and benefited from amenities, including parks, schools, libraries, and healthcare[119]. It also introduced a profit-share scheme, where workers with more than 5 years of service received “Co-Partnership Certificates” that granted annual dividends[120]. William Lever was also a vocal supporter of women’s rights. During an era when Women in Britain didn’t have the right to vote, female workers at Lever Bros. were given the same pay and promotion opportunities[121]. The Lever brothers were not unique in their business philosophy. Similar caring attitudes were also displayed by the Cadbury brothers, Joseph Rowntree, John Spedan Lewis, and Michael Marks, the founder of Marks and Spencer.

Henry Ford began his career at the Edison Illuminating Company. There, he remarked that by creating millions of well-paid jobs, Edison “has done more towards abolishing poverty than have all the reformers and statesmen since the beginning of the world.”[122] While at Edison, Ford also worked on his “horseless carriage”, which received encouragement from Edison himself. Ford’s first two companies were unsuccessful, but he persevered and in 1903 founded the Ford Motor Company. The profits from Ford’s early cars, the Model A and Model N, enabled investors to more than recoup their initial investments[123], but Ford is remembered for what came after, the legendary Ford Model T. By breaking down the complex manufacturing process into a series of simple tasks and using a moving assembly line to move the components to workers, Ford was able to drive down the cost of the cars significantly. The Model T sold for $850 (roughly $24,000 in 2020 dollars). Ford famously said that the Model T “will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one”. He was right. In 1913, Ford produced 170,000 Model T. This increased to over 200,000 in 1914, over 300,000 in 1915, and over 500,000 in 1916[124].

There was one problem for Ford, though. The moving assembly line, while helping to reduce costs, also made jobs extremely repetitive and unfulfilling. In 1913, the daily absence rate was 10%, and the annual staff turnover reached 370%[125]. This made scheduling difficult and increased the costs of training new staff. To resolve this, Ford doubled the wages to $5 per day ($130 per day in 2020 dollars). No one compelled Ford to increase wages other than market forces and the ability of workers to look for jobs elsewhere. If Ford wanted to make more cars and increase profits, he had to pay workers more. Ford’s experience showed that when productivity growth is sustained over the long term and labourers’ rights are protected, market forces will prevent capitalists from appropriating all the gains. This, however, doesn’t mean that the capitalists won’t try, and the ultimate split between labourers and capital owners still might not satisfy everyone’s definition of fairness.

At this point, it’s worth highlighting that Henry Ford was a complicated character. After raising the wages to $5 per day, Ford also set up a Sociological Department to ensure good moral character from his workers, which included personal habits at home. Many people today would frown at this, but it did have some benefits. If husbands (it was mostly men who worked at Ford’s factory back then) were spending all their wages at the bar and not providing for the family, their wives could go to the Sociological Department, and Ford would retain a proportion of the wages for childcare. This was an example of Henry Ford’s paternalistic instinct. His less controversial initiatives included setting up an employee savings and loan association to help workers build up wealth and a legal department that provided free assistance for home purchases, citizenship applications, and debt relief[126]. Ford Motor Company even offered classes that helped immigrant workers learn English. Henry Ford once wrote, “The trouble with a great many of us in the business world is that we are thinking hardest of all about the dollars we want to make. Now that is the wrong idea right at the start. If people would go into business with the idea that they are going to serve the public and their employees as well as themselves, they would be assured of success from the start.”[127]

Due to his paternalistic instinct and belief that he knew what was best for his workers, Henry Ford was fiercely anti-union. In 1932, 2,500 people marched on the River Rouge plant in a pro-union protest. Ford hired security workers and police officers, which led to violent clashes. Five workers died, and dozens were injured. In 1937, the United Auto Workers Union planned to hand out leaflets at an overpass leading to the River Rouge plant. Before they could do that, Ford’s security workers and police officers arrived and beat up the organisers[128]. Despite the violence, unionisation at Ford ultimately succeeded in 1941.

The impact of unions is hotly debated. Regardless of where you stand, one point that should be less controversial is that the decision on how to divide the economic gains of capitalism shouldn’t be determined by the capital owners alone. It’s great that we have enlightened business leaders, but not everyone is like William Lever or John Spedan Lewis. If capital owners are the only people deciding how the economic pie should be split, then there’s a danger that the slice for the workers will be just large enough to prevent an uprising, but no more. To ensure that the benefits of economic progress are broadly shared, we need to hear the voices of people from different parts of society. Today, this is even more important. Over the past few decades, digitalisation and its unique economic characteristics, such as network effect, meant that a few large companies have come to dominate certain markets. There is a risk that those giant businesses will use their economic and political power to shape outcomes in their favour rather than the broader society.

Capitalism’s Contributions to Progress

As we have seen so far, modern-day capitalism emerged over the past few centuries through the complex interactions of institutional development, technological progress, and social and cultural changes. The outcome is a period of rapid innovation, leading to extraordinary growth in labour productivity and economic output. To varying degrees, those gains have been shared broadly, albeit we can debate whether this has gone far enough and whether this has stopped in recent decades. Both characteristics, the existence of sustained economic growth and the fact that the elites didn’t appropriate all the gains, meant that the living standards for the average person have been transformed over the past two hundred years. Nothing like this has ever happened in human history.

In recent decades, it has become fashionable, especially among people already rich by global standards, to question just how important economic growth is, and whether it makes a difference to life satisfaction and happiness. Here, it’s important to distinguish that we are not asking the question of whether earning $1 million or $1 billion makes someone happier than earning $35,000, which is totally subjective. Rather, we are asking whether a country’s ability to deliver long-term broadly shared economic growth of 1, 2, or 3% per year is important to the things that we desire for a good life, such as accessible education and good healthcare. Here, the answer is a strong yes.

The first thing to note when discussing the importance of economic growth is that this is not just a monetary measure, even if it’s often communicated this way. Economic growth increases the goods and services that society can produce and provide to its citizens. It is a process of increasing material abundance, whereby what used to be luxuries are turned into things that are commonly available. Consider aluminium, today, we associate aluminium as a cheap, widely available material used in food and beverage packaging, construction, and the manufacturing of cars and aircraft. However, until the commercialisation of the Hall–Héroult process in the late 19th Century, producing elemental aluminium was extremely difficult and expensive, to the extent that aluminium was more expensive than gold and that Napoleon was said to have kept a few pieces of aluminium tableware for his more honoured guests[129].

Aluminium might be an entertaining example of how economic growth increases the availability of goods and services, but the process has worked for many other resources. Economic growth increased the abundance of food. Through mechanisation, selective breeding, and the applications of fertilisers and pesticides, agricultural yield has increased multiple-fold[130], allowing us to increase food supply faster than population growth and contributing to the falling real prices of many agricultural commodities over the long term. Those advancements did come with some nasty environmental impacts, but they helped billions of people to avoid starvation.

Capitalism’s ability to increase material abundance is acknowledged even by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In the Communist Manifesto, they wrote: “The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of Nature's forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground—what earlier century had even a presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labour?”[131]

Increasing material abundance, as well as the income people earn, has enabled social progress. In healthcare, improved sanitation and hygiene have made an enormous difference in people’s life expectancy. Safe drinking water and flushing toilets are obviously not free but require significant amounts of materials and investment. Recently, a 25-km sewage tunnel in London was completed at the cost of £5 billion[132]. In developed countries, we often take modern water infrastructure for granted, but income is still a hurdle to having those basic necessities in some parts of the world. Sometimes, even a small material improvement can make a big difference. In Mexico, researchers from the World Bank found that the government’s initiative to replace dirt floors with cement floors led to a 78% reduction in parasitic infestations, 49% reduction in diarrhoea, 81% reduction in anaemia and a 36% to 96% improvement in cognitive development[133].

Innovation has also contributed to improvements in healthcare outcomes. Medical discoveries, new vaccines and treatments, and advanced medical equipment don’t happen in a vacuum. They are made possible by millions of dedicated researchers and healthcare professionals who exist because economic progress has enabled many people to leave farming behind. Increasingly, medical breakthroughs require cutting-edge technology, such as genomic sequencing and advanced software, which rely on progress in other parts of the economy, including semiconductor manufacturing.

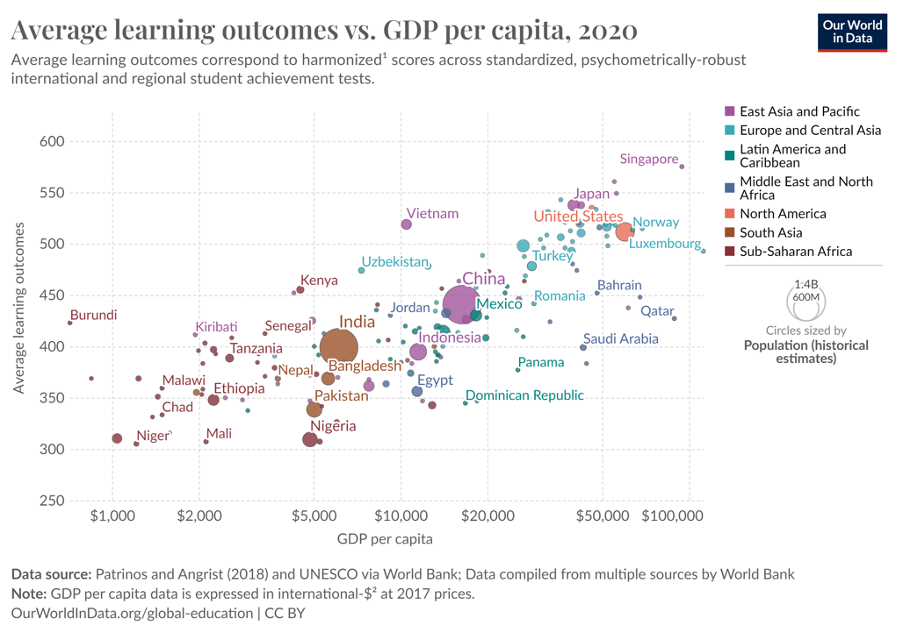

For education, economic growth makes a difference, too. As we have seen earlier, when people live close to subsistence levels, there is a lot of pressure on children to work. It’s an obvious but nevertheless important statement, when children are working, they are not studying. In many countries, governments provide most of the primary and secondary education, but that doesn’t make education free. Building schools, purchasing books, and paying teachers still costs money. Those are funded through tax, which ultimately comes from people’s pockets. A prosperous and growing economy makes taxation and funding public services much easier. We find a strong positive correlation between per capita GDP and learning outcomes.

Economic growth also affects how we feel and behave. Yes, money can’t necessarily buy happiness, but the lack of it can make life very stressful, degrading, and dangerous. In his book Development as Freedom, Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen told a heartbreaking story from his childhood, where a Muslim day labourer in his predominantly Hindu neighbourhood was knifed and killed by street thugs. The day labourer’s wife told him not to go work in the Hindu neighbourhood because those were the days of communal riots before the independence and partitioning of India and Pakistan. However, the day labourer had little choice because his family was poor and starving. The prize of his poverty turned out to be death[134]. While the lack of money doesn’t result in such extreme outcomes most of the time, small setbacks such as a broken car tyre or a sudden illness can still make life very unpleasant if they lead to financial distress. The psychological burdens can often manifest into poor health and life outcomes in complex ways. While we can criticise live satisfaction surveys for their subjectivity, we generally find people in rich countries happier than those in poorer countries[135].

When there’s broad-based economic growth, people feel their lives are getting better. A lack of growth gives that sinking feeling. Neurological studies suggest that human brains are wired in a way that the satisfaction we get from a constant level of living standards diminishes over time[136]. In other words, we quickly get used to things and strive for more. While this growth mindset can, at times, work against our interests, it is also a powerful driver of progress. Some religions teach the virtues of detaching oneself from material gains, which can be beneficial in moderation, but I think it’s unwise to rely on abstinence to overcome our biological traits. Instead, delivering broad-based economic growth together with an acknowledgement towards enjoying what we have might be the best way to promote a happy and inclusive society.

Benjamin Friedman powerfully argued that economic growth brings moral positives. "Economic growth - meaning a rising standard of living for the clear majority of citizens - more often than not foster greater opportunity, tolerance of diversity, social mobility, commitment to fairness, and dedication to democracy."[137] If we don’t acknowledge those positive impacts, we are likely to undervalue the importance of economic growth. Martin Wolf made similar arguments, suggesting that the rise of populism in recent years was a direct result of economic policies failing to improve people’s lives. He wrote, “People expect the economy to deliver reasonable levels of prosperity and opportunity to themselves and their children. When it does not, relative to those expectations, they become frustrated and resentful.”[138]

At this point, it’s worth saying that while economic growth is an important enabler of social progress, it’s not the only thing that matters. Many observers have pointed out that while people in the U.S. enjoy a very high level of income per capita, their life expectancy is lower than that of some countries with significantly lower per capita income. Evidently, there are other factors beyond income that influence the quality of life. Nevertheless, just because other factors that affect the quality of life exist doesn’t render economic growth meaningless. Economic growth matters in itself, and it helps facilitate other things that are important for social progress, such as the government’s ability to finance social services. Amartya Sen argued that a constructive view to examine development is through the lens of enhancing people's capabilities and freedom to live the life they desire[139]. However, Sen also acknowledged that income and economic growth play a positive role in this process[140].

Summary

In this article, we have seen how humanity has made enormous progress over the past two hundred years across different domains, including material living standards, health outcomes, education attainments, and growing respect for one another. Furthermore, this progress has been a paradigm shift compared to the preceding millennia, where the life expectations for the average person had barely changed.

I argued that the emergence of capitalism has made a positive contribution towards human progress. This came through a two-step process. First, capitalism, by being very efficient at allocating resources, has increased material abundance. This increasing abundance is vital to improving living standards and supporting social progress. Second, as a society, we have made the intentional choice that this material abundance should be broadly shared so that many people can benefit from it. This is a radical departure from the past when the elites were able to capture all the gains. It’s important to acknowledge that the second step doesn’t automatically follow from the first, and there have been many instances in human history where it didn’t. To continue human progress, we must take both steps, not just one.

[1] Edelman, Edelman Trust Barometer 2020

[2] James O’Toole, Enlightened Capitalists: Cautionary Tales of Business Pioneers Who Tried to Do Well by Doing Good, (HarperCollins, 2019)

[3] Michael Sandel, Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do, (Penguin Books, 2009), p. 216.

[4] Wikipedia contributors, “Rainhill Trials,” Wikipedia, December 18, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rainhill_trials.

[5] J.C. Jeafrreson and William Pole, The Life of Robert Stephenson, Vol. I. (Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts and Green, 1864), 2.

[6] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 7

[7] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 20

[8] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 30

[9] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 55

[10] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 66

[11] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 117

[12] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 124

[13] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 169

[14] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 172-180

[15] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 185

[16] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 209

[17] L.T.C. Rolt, “Building the London & Birmingham Railway” in George and Robert Stephenson: The Railway Revolution, (Amberley Publishing, 1984)

[18] Library of Birmingham, “A Brief History of Curzon Street Station - Library of Birmingham,” n.d., https://web.archive.org/web/20130629144655/http://www.libraryofbirmingham.com/article/historyofcurzonstreetstation/curzonstreetstation.

[19] Jaefrreson and Pole, The Life of Robert Stephenson, p. 267

[20] Jaefrreson and Pole, The Life of Robert Stephenson, p. 269

[21] Leigh Shaw-Taylor and Xuesheng You, The development of the railway network in Britain 1825-1911, 2018

[22] L.T.C. Rolt, “George Stephenson – The Closing Years” in George and Robert Stephenson: The Railway Revolution, (Amberley Publishing, 1984)

[23] L.T.C. Rolt, “The End of an Era” in George and Robert Stephenson: The Railway Revolution, (Amberley Publishing, 1984),

[24] Jaefrreson and Pole, The Life of Robert Stephenson, p. 7

[25] Jaefrreson and Pole, p. 13

[26] Bank of England, A Millennium of Macroeconomic Data [dataset], 2023, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/research-datasets

[27] “Poverty in the Rich World When It Was Not Nearly so Rich,” Center for Global Development, n.d., https://www.cgdev.org/blog/poverty-rich-world-when-it-was-not-nearly-so-rich.

[28] Angus Maddison, Contours of the World Economy, 1-2030AD, (Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 69

[29] Vaclav Smil, Growth – From Microorganisms to Megacities, (The MIT Press, 2019)

[30] Angus Maddison, Contours of the World Economy, p. 30