Enlightened Businesses - Part 4: Costco Wholesale

The story of a retail giant whose success comes from a relentless focus on lowering prices for customers and treating workers with respect.

**This post is not investment advice. Please see the full disclosure on the About page**

In Seattle in the early 1980s, two entrepreneurs raised $7.5 million in equity funding to start a business. Within three years, the company hit $1 billion in revenue. A decade later, revenue topped $10 billion. Today, the company operates across North America, Europe, and Asia, has more than $200 billion in revenue, and generates a return on equity of 25%. It has more than 70 million loyal members and boasts an annual retention rate of 90%. You might think this is a tech company, but no, this is a brick-and-mortar retailer by the name of Costco Wholesale.

Costco is a retail behemoth. Nearly a third of US consumers shop at Costco, and people in Europe and Asia appear just as keen. On the opening day of Costco’s first warehouse store in Mainland China, shoppers queued for three hours to get into the parking lot. In Iceland, where Costco only entered in 2017, more than 70% of the country’s population is a Costco member.

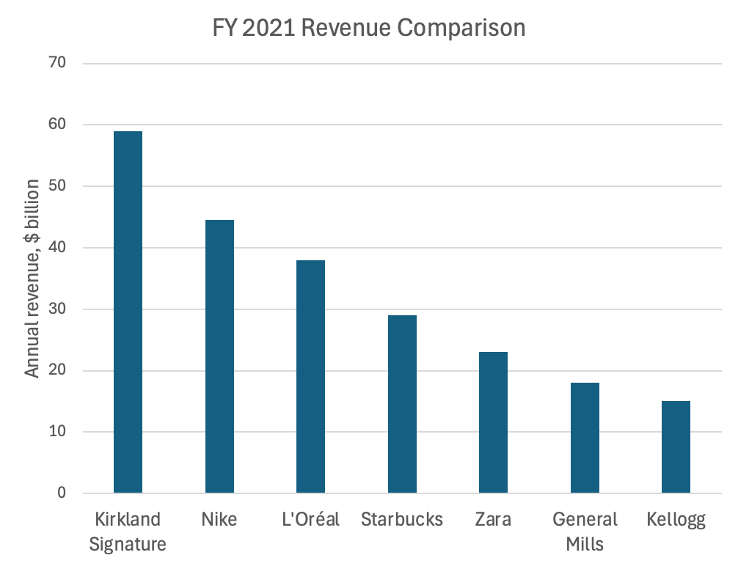

Costco's scale is staggering. In 2021, its private label, Kirkland Signature, generated $59 billion in revenue. If it were a standalone company, its revenue would be higher than that of Nike, L’Oréal, and Kellogg. Costco is not a place just for groceries and household items. It also sells cars, provides kitchen fitting, HVAC installation, and travel services, and is one of the world’s largest sellers of hearing aids and optical glasses. In 2019, Costco filled 33 million prescriptions, helping millions of people lower their drug bills.

You can’t just walk into a Costco warehouse and buy something off the shelf. To shop there, you must be a member. Worldwide, more than 70 million people pay Costco for this privilege. Why, you might ask. It’s for the simple reason that Costco offers some of the lowest prices you can find. The membership fee, around $60 per year, more than pays for itself. What’s more, Costco’s low prices don’t come at the expense of quality, its employees, or its vendors. For four decades, Costco has succeeded by sticking to its simple Code of Ethics:

Obey the law.

Take care of our members.

Take care of our employees.

Respect our suppliers.

If we do these four things throughout our organization, then we will achieve our ultimate goal, which is to:

5. Reward our shareholders.

History

Sol Price

Costco was founded in 1983 in Seattle by Jeff Brotman and Jim Sinegal, but the company’s history stretches back to a man called Solomon Price, who started a chain of membership stores called FedMart in the 1950s. FedMart was very successful, but Price eventually lost control of the company. After he was ousted from FedMart, Price and his son, Robert Price, set up Price Club. Price Club provided the inspiration for Costco. In fact, Jim Sinegal worked with Price at both FedMart and Price Club. In the early 1990s, Price Club and Costco Wholesale merged, so, a direct line can be traced from FedMart, to Price Club, to Costco. All three companies share similar business philosophy and culture, notably, always providing the best values to customers.

Solomon Price, or Sol Price as he’s commonly known, was born in the Bronx, New York, in January 1916. Price’s parents were Jewish immigrants who arrived in America before World War I. His mother, Bella Barkin, was born in the district of Minsk, then a region of Imperial Russia, in 1891, and was the youngest of five daughters. Shortly after her birth, Barkin’s mother was widowed and the family struggled to make ends meet. In the early 1900s, Barkin was sent to America in search of a better life. She settled in the Lower East Side of Manhattan and found work in the Garment District. There, she met Susuch Pruss, who would later change his name to Sam Price. Pruss also came from the district of Minsk and emigrated to America in 1906. In 1910, Bella Barkin and Sam Price were married.

Sol Price was a mischievous child at school, but he was very clever. He skipped two grades and entered high school at the age of thirteen. Price’s teacher once told his mother that her son would become a gangster or someone who would do much good. Thanks to his parents, Price would end up as the latter. Bella and Sam Price were labour activists and fought for workers’ rights and civil liberties. Price grew up in a household where political discussions were frequent, and those early discussions left a deep impression on him.

Just before the Great Depression, the Price family moved to San Diego. Sam Price contracted tuberculosis, and his doctor recommended he move to California. In 1938, Sol Price graduated from the USC School of Law, finishing in the top 10% of his class. The same year, he married Helen Moskowitz, his life partner for the next seventy years. After graduating, Price’s father-in-law introduced him to Jacob Weinberger, a well-respected attorney in San Diego, who permitted Price to use his library and keep one-third of the money he brought in.

During World War II, Price was exempt from the draft because of his drooping eyelid and partial blindness in his left eye. Instead, he continued practising law while working the afternoon and evening shifts in the engine maintenance department of Consolidated Aircraft, which was building B24 Liberator bombers at Lindbergh Field. Throughout the war period, Price would practice law between 8:00 am and noon, before going to Lindbergh Field and work at Consolidated Aircraft until 11:15 pm. As World War II drew to a close and having established his reputation as a lawyer, Price started his own law firm.

FedMart

Throughout the 1950s, San Diego experienced strong population growth and an economic boom. People were drawn to the city by the pleasant climate and good job prospects with the Navy and the military. The economic expansion benefited the city’s retail industry. At the time, most retail businesses were traditional department stores located in prime shopping areas and carried a full range of products to cater for as many customers as possible. The stores were beautifully decorated and sales clerks provided personal shopping services. To cover the large overheads, stores charged high mark-ups and adhered to the Fair Trade laws, which prevented retailers from selling goods below the manufacturer’s minimum retail prices.

Sol Price entered retail almost by accident. One of his clients and good friends was Mandell Weiss. Weiss and his business partner Leo Freedman ran a successful jewellery business called Four Star Jewelers. Four Star, in addition to having its own retail business, also sold products wholesale to other retailers. One of its top wholesale clients was a Los Angeles-based business called Fedco. The company was founded in 1948 by eight hundred US Post Office employees who wanted to leverage their buying power and purchase goods directly from wholesalers. Despite being a non-profit, membership store that only catered to Federal employees, Fedco became wildly successful. In fact, Fedco had 5,000 customers living in San Diego who would travel 200 miles to shop at Fedco because of the bargain prices. Price, Weiss, and Freedman immediately recognised the potential. It happened that Price was trying to find a tenant for a warehouse owned by his mother-in-law. So, he rented out the warehouse with the intention of forming a JV with Fedco and bringing the concept to San Diego. However, Fedco had no intention of expanding into San Diego and twice rejected Price’s proposal. Undeterred, Price decided to open the store himself.

In 1954, with an initial investment of $50,000 (Price contributed $5,000), FedMart opened for business. FedMart copied Fedco’s model almost exactly, but whereas Fedco was a non-profit organisation, FedMart was combined with a for-profit entity, Loma Supply. Initially, shoppers had to be military or federal employees and purchase a $2 lifetime membership. The membership requirement allowed FedMart to circumvent the Fair Trade laws and sell goods below the manufacturer’s minimum retail prices. FedMart’s model was a stark contrast to the department stores. FedMart opened late during the week to make it more convenient for customers. Products were sold in makeshift fixtures rather than display cabinets. With the exception of jewellery, the store was self-service with a central cash register. While FedMart sold many categories of goods, including clothing, appliances, mattresses, and liquor, the selection was limited to improve the efficiency of logistics and operations. Everything was done with cost in mind.

From the very first store, Price operated his business with an ethical philosophy based on the Golden Rule. He believed FedMart had a fiduciary duty to its customers. This means being very honest with customers and providing them with the best value. While many companies made similar statements, Price walked the talk. For example, FedMart refused to engage in the popular practice of luring shoppers into the stores using loss leaders because that would have required the company to make extra profits on other items. Price believed this was tantamount to treating customers as fools. In another instance, Price became angry when he found out that a line of consumer electronic products was sold out at a 50 per cent gross margin. This was double the store’s usual margin and Price was upset that the savings weren’t passed onto the customers.

For many employees, FedMart offered an opportunity for a better future. When FedMart expanded to San Antonio, Texas, it paid employees double what competitors were offering because Price believed the prevailing wages weren’t sufficient for a decent standard of living. Price even fought against racial segregation. When he found out that the mortgage for FedMart’s Dallas store contained a term that required segregated bathrooms, Price went to the lender and said FedMart wouldn’t comply. The lender relented.

Price even extended the principle of fair dealing to suppliers. In one instance, FedMart was selling hosiery for $3.99 when Price came up with the idea to reduce the price to $2.99. FedMart would give up 50 cents if the supplier pitched in the other half. The supplier agreed, but six months later, the new price made little difference to sales volume. Price went back to the supplier and refunded them their 50 cents contribution.

Price’s business principles were summed up in four simple statements.

Provide the best possible value to the customers, excellent quality products at the lowest possible prices.

Pay good wages and provide good benefits, including health insurance to employees.

Maintain honest business practices.

Make money for investors.

Shareholders came last in the list not because they were the least important. Rather, Price believed if FedMart can take care of its customers and employees and stick to honest business practices, then profits should result automatically. He was right. The first FedMart store generated $3 million in sales in the opening year, three times the original target. FedMart then opened a second store in Phoenix, Arizona, which was equally successful, before expanding to Texas. In 1959, five years after the first store opened in San Diego, FedMart generated $26 million in sales and a profit of $470,000. That year, the company went public, raising $2 million in capital.

FedMart’s success attracted the attention of other retailers. One famous early visitor to FedMart’s stores was Sam Walton, the founder of Wal-Mart. Walton and Price would become good friends, and in his autobiography, Made In America, Walton wrote, “I guess I’ve stolen - I actually prefer the word “borrowed” - as many ideas from Sol Price as from anybody else in the business.” In 1962, in a Cambrian explosion of US retail, Wal-Mart, Kmart, and Target all opened their first store. By the early 1970s, competitive pressure was taking a toll on FedMart’s performance.

In 1974, Sol and Helen Price travelled to Europe for vacation. Sol Price used the opportunity to visit retail businesses across the continent. At Karlsruhe, Price met Hugo Mann, whose Wertkauf stores were trying to replicate Carrefour’s hypermarché format in Germany. Price and Mann got along well, and Mann expressed an interest in investing in FedMart. Mann’s proposal was a good fit for FedMart. The investment would enable FedMart to accelerate store openings and allow some early investors to cash out. The proposal was helped by the fact that Mann was not a direct competitor to FedMart. In August 1975, Mann acquired a 64% stake in FedMart for $22 million.

Unfortunately for Price, Mann had other intentions. While he was pleasant throughout the negotiation, as soon as the ink was dry, Mann revealed his true character. In the first board meeting after the merger, Mann went on a 90-minute rampage criticising Price and FedMart. In December 1975, Mann ousted Price from FedMart. Without Price, FedMart’s fortune quickly declined. In 1982, Mann closed FedMart and leased 35 locations to Target.

Price Club

Sol Price was 59 years old when he was ousted from FedMart. Others in his position might have contemplated retirement, but not Price. With help from his son, Robert Price, Sol Price immediately began looking for an opportunity to get back into business. The Prices didn’t want to clone FedMart, but there were certain aspects of the business they liked. Top of that list was the International Distribution Company, FedMart’s distribution subsidiary that sold thousands of products to individual FedMart stores. IDC made a profit by charging a small markup for receiving, stocking, selecting, and delivering merchandise to FedMart stores. Sol and Robert Price believed there could be demand for IDC’s services beyond just FedMart stores.

In 1976, Sol and Robert Price founded Price Club, a wholesale business catering to small businesses. At the time, most small businesses procured their merchandise from suppliers who specialised in certain product categories. They charged high fees for added services including order taking, delivery, and credit. The Prices believed that by pooling together the purchasing power of hundreds or even thousands of small businesses and selling merchandise from a large, no-frills warehouse, they could offer much lower prices than traditional suppliers. Price Club would charge business owners an annual membership fee of $25 to shop at its warehouse. By the summer of 1976, the Prices raised $2.5 million in equity funding, arranged a $4 million line of credit with Bank of America, and signed a 10-year lease for a warehouse on Morena Boulevard.

The initial reception for Price Club was lukewarm at best. It turned out that many business owners weren’t ready to give up the conveniences offered by their existing suppliers just to save a bit of money. Price Club’s sales came in way below expectations. The situation was so dire that employees were asked to park their cars at the front to show the company was open for business. Then came a good piece of fortune. The San Diego Credit Union enquired if its members could shop at Price Club. Most members were not business owners, and the Prices worried that by allowing the general public to shop at Price Club and purchase goods at wholesale prices, they would anger their business customers. After much debate, they agreed that union members could shop at Price Club but had to pay 5% above wholesale prices. In exchange, Price Club would waive the membership fee.

What happened next surprised the Prices. The credit union members signed up in large numbers, and when they realised that they could save 5% by becoming business members, they started to look for family members or people they knew who were business owners. As a result, Price Club’s business memberships unexpectedly grew. Over time, Price Club formalised the system by introducing a two-tier membership scheme. Business members paid a $25 annual membership fee and were issued a plastic card for themselves and two more cards for others in their business. Group members paid no membership fee, were issued a paper membership card for themselves and their spouses, and paid the advertised price plus 5%.

This new arrangement turned around Price Club’s fortune. Business flourished and by June 1977, the company made its first monthly profit. By the end of 1977, Price Club opened three new stores, two in Arizona and one in San Diego County. In 1979, Price Club went public, not because it needed money, but because the number of shareholders crossed the 500 mark, which necessitated making filings with the SEC. In 1982, Price Club’s shares were listed on the NASDAQ.

Like FedMart, Price Club’s success attracted wider attention. In 1978, a man named Bernard Marcus turned up at Price Club’s Morena Boulevard warehouse. He just got fired as the President of Handy Dan, a chain of home improvement stores. Sol Price took Marcus around and advised him to end his lawsuit for wrongful dismissal and start his own company. Next year, Marcus and his partner Arthur Blank opened the first Home Depot store in Atlanta. Marcus not only took Price’s advice but he and Blank borrowed many ideas from Price Club. Home Depot’s business philosophy, which emphasises providing the best customer experience, being the lowest cost operator, and treating employees well, is remarkably similar to Price Club. Today, Home Depot has more than 2,000 stores, generates $150 billion in revenues, and commands a market cap of more than $300 billion.

Sam Walton also made repeated visits to Price Club warehouses. On one occasion, the security guard at the Morena Boulevard warehouse confiscated Walton’s recorder and tape. When Robert Price found out about this, he sent the recorder and tape back to Walton, with none of the recordings scratched out. In 1983, Walton opened the first Sam’s Club. However, the most consequential “imitator” happened to be a young lawyer from Seattle.

Costco Wholesale

Jeff Brotman was a Seattle lawyer who split his time between a law practice and his family’s retail interest. On a trip to France, he became fascinated by the French retailer Carrefour, which was pioneering the hypermarché concept. Upon his return to Seattle, his father, Bernie Brotman, told him about Price Club. The Brotmans enquired if they could open a Price Club franchise in Seattle and the Northwest. Price Club executives studied the proposal and then rejected it.

Undeterred, Jeff Brotman decided to venture alone. He called Jim Sinegal, who by then had left Price Club and was advising suppliers who wanted to sell to big box stores like Price Club. Sinegal began working part-time for FedMart in 1954 while studying for a degree at San Diego State College. He would work his way from the stock room to become the Head of the International Distribution Company, the FedMart subsidiary that was the inspiration for Price Club. Brotman and Sinegal met in Palm Springs and the two got along well. Over the next several months, they drew up a business plan for a new retail business, taking many inspirations from Price Club. They named the company Costco Wholesale, and it would sell a narrow selection of curated, high-quality items at a low markup in no-frills warehouses. Members would pay an annual fee to shop at Costco. And like Price Club, Costco would treat its employees well, emphasise internal promotion, and work collaboratively with its vendors.

In 1983, Brotman and Sinegal raised $7.5 million in equity funding for Costco Wholesale. The first warehouse was opened in Seattle in September of that year. Ahead of the opening, the Costco management team proactively reached out to Teamsters, inviting them to form a union. The Teamsters representatives spent a week at the warehouse and then disappeared. It turned out that Costco employees were treated so well that they showed no interest in unionising.

The first Costco warehouse was an enormous success. The original plan was for Costco to open twelve warehouses in the Northwest, each generating $80 million of sales per year at a 3% margin. However, Brotman and Sinegal quickly realised that the opportunity was much bigger, so they raised another round of funding to accelerate growth. In 1985, Costco opened new stores in California and Canada, followed by Mexico in 1992, the UK in 1993, and South Korea in 1995. At the same time, Costco expanded into new product categories while keeping the overall SKUs per warehouse to less than 4,000. Fresh produce, including meat and bakery items, was introduced in 1987 while the famous rotisserie chicken (Costco now sells more than 100 million rotisserie chickens per year!) was introduced in 1995.

The introduction of fresh produce proved important. Price Club was reluctant to embrace fresh produce, which put it at a competitive disadvantage. As Costco and Sam’s Club expanded aggressively, Price Club began to lose share. At the same time, Sol Price started showing more interest in real estate, buying up land around Price Club stores. The move into real estate was not taken well by shareholders and caused internal tension among the management team. Rick Libenson, Price Club’s Chief Merchandising and Operating Officer, and Giles Bateman, Chief Finance Officer, left in 1988 and 1991 respectively. In addition, personal tragedy struck in 1989 when Aaron Price, Robert Price’s son, died at the age of fifteen due to a brain tumour.

The cumulation of those events led Sol and Robert Price to consider selling Price Club. There were two realistic options: Sam’s Club and Costco. They ultimately decided to merge with Costco because the cultures were more compatible, especially on employee treatment. It also seemed fitting given that Jim Sinegal was one of Sol Price’s first employees. In 1993, Price Club and Costco merged, forming PriceCostco. Costco shareholders received 52% of the combined entity and Price Club shareholders received 48%. Jim Sinegal became the CEO while Robert Price took the role of Chairman. The management setup proved short-lived. Robert Price wasn’t quite ready to give up operation responsibilities, so the following year, PriceCostco engineered an exit for Robert and Sol Price. It spun out certain real estate assets into a separate company called Price Enterprises and gave the Prices the right to run the warehouse retail business in Central and South America under PriceSmart, which continues to operate to this day.

When Price Club and Costco merged, the combined company had 195 stores across the US, Canada, and Mexico, with annual sales of $15 billion. The company was valued at just over $2 billion. What happened next probably exceeded management’s own expectations. Over the following three decades, Costco added more than 600 warehouses across North America, Europe, and Asia. Its sales grew by 15-fold and its share price increased by 100-fold, a compounded annual return of 16% for 31 years. One person who spotted the potential was an investor by the name of Charlie Munger, who first invested in Costco in 1997 and was a director of the board from 1997 to 2021.

Playbook

A key contributor to Costco’s success is its focus on customers. Its mission is "To continually provide our members with quality goods and services at the lowest possible prices.” This is an extension of Sol Price’s philosophy, which Jim Sinegal took with him to Costco. Like FedMart and Price Club, Costco doesn’t offer loss leaders. It also keeps its markup low, with a gross margin of 11% for most of its history. This compares to Target's 27%, Walmart's 24%, and Carrefour's 20%. Costco could easily increase its margin without customers knowing, but Sinegal explained why the company doesn’t do this. "You could raise the price of a bottle of ketchup to $1.03 instead of $1, and no one would know. Raising prices just 3% would add 50% to our pretax income. Why not do it? It's like heroin. You do it a little bit, and you want a little more. Raising prices is the easy way.”

Keeping markup consistently low also helps to build trust with vendors. Vendors know that when Costco negotiates lower prices, those prices would be passed onto customers rather than pocketed by Costco. Lower prices for customers should spur higher demand, which will benefit vendors. Also, because Costco stocks fewer than 4,000 SKUs, compared to 50,000-100,000 SKUs typical for most retailers, its buyers only manage a handful of relationships and have a deep understanding of their vendors. They know the cost structure of the merchandise, track the commodity prices of the raw materials, and sometimes advise vendors on how to cut costs.

Costco’s scale does provide some benefits when negotiating with vendors. A good example is payment processing. While this has never been disclosed, trade journals suggest that card companies pay Costco to process payments rather than the other way around. Sometimes, Costco would backwards integrate into production if this can help drive down costs. For instance, Costco has several lens manufacturing facilities, helping to reduce the cost of vision lenses by over 20%. In 1997, Costco opened a meat processing facility to produce Kirkland Signature meatballs, reducing costs by 40%.

Finally, there are the little things that demonstrate Costco’s commitment to members. When one of Costco’s tyre suppliers gave the company a $1 million rebate, Costco tracked down all the customers who purchased a tyre and passed the rebate to them. If you are a Costco Executive member, which entitles you to a 2% cashback on purchases, but you don’t spend enough to justify the higher upfront membership fee, Costco will refund the difference.

While Costco offers low prices, it also maintains very high standards for product quality, which extends to Costco’s Kirkland Signature products. For instance, all Kirkland Signature coffee is Fair Trade certified and the Kirkland Signature House Blend is actually roasted by Starbucks. Costco wants to ensure its store-cooked rotisserie chickens are as fresh as possible, so each container has a time stamp, and any unsold chickens after two hours are pulled from the shelf and harvested for other uses, such as soup and salad. It’s this commitment to quality that allows Costco to not only sell daily necessities, but also Rolexes, diamond engagement rings, and fine Bordeaux wine.

Taking care of employees is important to Costco’s success. Costco’s average hourly wage is $26, compared to $19.50 at Walmart. Employees, including hourly workers, receive retirement and healthcare benefits, the latter Costco provides predominantly through self-insurance. As a result, after the first year, Costco’s staff turnover rate amongst hourly workers is only 7%, compared to 20% for the rest of the retail industry. Treating employees provides numerous benefits, including a very low shrinkage rate and lower costs in recruiting and training new workers. This was well documented by the HBR article The High Cost of Low Wages, which compared Costco’s and Walmart’s approach to employees.

The best analogy of Costco is an orchestra. A typical orchestra has up to 100 musicians, all specialising in different instruments. Individually, the musicians can’t perform Symphony No. 9, but when they work together, they can delight the audience. Likewise, Costco’s success is not due to a single activity, but hundreds of decisions, each with its own trade-off, that all work together harmoniously. The beautiful music Costco plays is delighting its members with great quality products at amazing prices. And by doing this so well, it satisfied its ultimate objective of rewarding shareholders.

Sources:

Robert E. Price, Sol Price: Retail Revolutionary & Social Innovator, San Diego History Center, 2012

Coriolis Research, Understanding Costco, 2004

New York Times, FedMart to go Private, Feb 19 1981

New York Times, Target to Reopen 35 Fedmart Stores, Aug 7 1982

Home Depot 2023 Annual Report

David Schwarts and Susan Schwartz, The Joy of Costco, Self Published

Jim Sinegal Provost Lecture

Adam Bryant, Costco Set to Merge with Price, NYT, 17th June 1993

Ben Ryder Howe, How Costco Hacked the American Shopping Psyche, NYT, 20th August 2024

Costco Code of Ethics

Costco Acquired Podcast

Wayne F. Cascio, The High Cost of Low Wages, Harvard Business Review, 2006